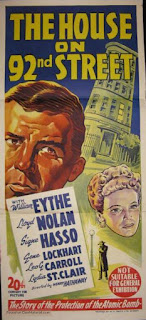

House on 92nd Street, The (1945)

Director: Henry Hathaway

Honors:

A month after the United States had dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, and mere days after Japan issued its unconditional surrender,

effectively ending World War II, is released a motion picture shrouded in in a

backstory as if it was a secret, not to be seen until the war was won. This

noir picture about domestic espionage would capture the imaginations of audiences

yet to come down from the high of finally winning the war. Produced with the

cooperation of the FBI, this feature reminds viewers to keep an eye open for

traders in the midst, for even the smallest things could carry large

consequences.

The House on 92nd

Street is a film noir spy picture presented in semi-documentary style about

an American double-agent who infiltrates a secret string of Nazi spies in the

early days of World War II. The film represents the tale as a documented true

story about a bright college student of German family heritage, Bill Dietrich

(William Eythe). Approached by Nazi spies because of his ancestry and IQ, this

American born student informs the FBI of his encounters. FBI Agent George

Briggs (Lloyd Nolan) concocts the idea to use the young man as a double-agent

to delve into the secret ring of Nazi espionage. Dietrich’s actions have him

working for his contact Elsa Gebhardt (Signe Hasso), a Nazi agent moonlighting

as a New York dress designer, who speaks for an unseen Nazi authority figure

known only as “Mr. Christopher.” Through the dangerous and deadly game played

by Detrick and Briggs, FBI find their Mr. Christopher and bring down the Nazi

infiltration, discovering that the Germans were gathering information on the

American research on the atomic bomb, servicing as a wakeup call for audiences

of the domestic dangers to keep eyes open for.

At the time of the film’s production and release the feature was far

more gripping and relevant to the modern events as the war had literally just

concluded days before. It is rather amazing how the filmmakers quickly molded

the movie to be so very current with the recent use of the atomic bomb that had

brought the conflict to a sudden and crippling conclusion. However now

separated with time and history since these historical events we can observe

the film as pandering to the FBI. After all it was with the FBI’s cooperation

that aided in the inspiration of the plot and supplying of numerous agents as

consultants and even as extras for production. The film’s tale is a bit too

clean and tidy for such an event in which it depicts and paints the FBI as a well-oil

machine of efficiency in carrying out justice during a time of heightened

strife.

At the time of the film’s production and release the feature was far

more gripping and relevant to the modern events as the war had literally just

concluded days before. It is rather amazing how the filmmakers quickly molded

the movie to be so very current with the recent use of the atomic bomb that had

brought the conflict to a sudden and crippling conclusion. However now

separated with time and history since these historical events we can observe

the film as pandering to the FBI. After all it was with the FBI’s cooperation

that aided in the inspiration of the plot and supplying of numerous agents as

consultants and even as extras for production. The film’s tale is a bit too

clean and tidy for such an event in which it depicts and paints the FBI as a well-oil

machine of efficiency in carrying out justice during a time of heightened

strife.

Directed by Henry Hathaway, The

House on 92nd Street presents its tale in an interesting manner.

Hathaway, an Academy Award nominated director, was beginning to delve into a

more noir style to his recent storytelling, but as an added twist this story

was penned in a manner that presents the plot to be a documented true event.

The film opens in a documentary style before falling into a more recognizably common

narrative storytelling with the continuing voice over to guide the audience

through. This new documentary styling would earn Hathaway some critical praise

and began a trend in Hathaway’s productions seen within several of his future films.

Actual footage from FBI files are cut into the film to manifest the

agency’s actions of cracking down on spies, aiding in the narrative’s realism.

The conclusion would also cut together newsreel footage of actual captured

German spies within the American population adding to the documentary style the

earlier sections of the film began. Not only did this impact naïve audiences

into thinking that what they were watching was historically actuate events, but

helped to build up a sense of trust for the US government and its powerful

agencies.

The truth is that the story was based on a series of actual events

including American double agent Willian G. Sebold and bringing down of the

Duquesne Spy Ring in 1941. These real events would be penned and pachagedin a

more cleaned up tale that was both FBI and J. Edgar Hoover approved, painting the

Bureau in the best of lights. In the film the FBI’s actions were done so

cleanly and with precision that it would wow more naïve viewers, but most

likely covered any ugly blemishes that FBI are known to have been when carrying

out some cases.

William Eythe stars as Bill Dietrich, the American

hero who put his life on the line to help his country. This would be perhaps

the best-known performance of Eythe, who was a far lesser supporting actor

before the war. He had moved his way into better roles when many of the best

actors were taken in by the war efforts. But with the end of the war Eythe’s

career would take a quick fall to B status as Hollywood’s stars returned and

bright new actor emerged.

Lloyd Nolan is featured as Dietrich’s primary FBI

contact in the feature, in a way representing the entire Bureau to the audience

in this picture. This too was one of Nolan’s more memorable performances for

this lesser known actor as his appearance and acting style lacked the grace of

a leading man.

Lloyd Nolan is featured as Dietrich’s primary FBI

contact in the feature, in a way representing the entire Bureau to the audience

in this picture. This too was one of Nolan’s more memorable performances for

this lesser known actor as his appearance and acting style lacked the grace of

a leading man.

Signe Hasso depicts the film’s

primary antagonist Elsa Gebhardt, the contact of major Nazi spy ring based out

of New York City. Once dubbed “the next

Garbo,” this Swedish born actress’ accent helped to make her a believable foreign

woman of style, but would not lend to actually making her a superior actress.

Her forced villainous flair more likely was inspired by poor writing, the very

same writing that made the FBI look as the shinning beacon of all American

morals. However, Hasso’s performance did not aid in manifesting anything better

than a B-film baddy.

Feeding off the nation’s emotional

high of victory in both Europe and Japan this film generally was praised by audiences,

while meeting mixed reviews from critics at the time of its release. I small

glimpse into the inner workings of the FBI was a bit an eye opener for many

viewers. Observing a representation of

how the agency investigates cases may be nothing too new, but there are moments

that shared previews of impressive means by which they worked, including the

massive fingerprint catalogue, which works in the manner like am archaic

computer of sorts. Critics were not all too thrilled, but still managed to feed

the film some positives marks, perhaps also because of the recent end of World

War II.

The film would be honored at the

1946 Academy Awards with the honor for Best Story, but in time the film quickly

fell out of the minds of audiences. Somehow a sequel would be produced in

1948’s The Street with No Name with

Lloyd Nolan reprising the role of Agent Briggs, directed by Willian Keighley.

It’s tale about the agency fight against gangster would utilize the similar

documentary style, but would only meet mixed reviews at best.

Looking back The

House on 92nd Street serves merely as a clean package that for may

have been the first look into the world of the FBI’s on a more sophisticated level

than the usual G-man type of story. Its plot is a glorified fictionalization of

actual events, which although interesting, prove to be too clean for even a

Hollywood script. It serves as a capsule into the past, but gets swallowed up

by far more intellectually and emotionally moving films of the post- World War

II era. It was worth a watch, but something most will not revisit.

Looking back The

House on 92nd Street serves merely as a clean package that for may

have been the first look into the world of the FBI’s on a more sophisticated level

than the usual G-man type of story. Its plot is a glorified fictionalization of

actual events, which although interesting, prove to be too clean for even a

Hollywood script. It serves as a capsule into the past, but gets swallowed up

by far more intellectually and emotionally moving films of the post- World War

II era. It was worth a watch, but something most will not revisit.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment