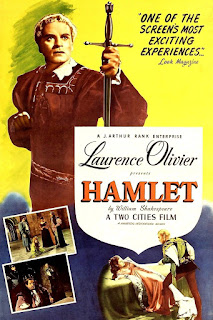

Hamlet (1948)

Director: Laurence Olivier

Starring: Laurence Olivier

Honors:

Academy Award for Best Art Direction (Black and White)

Academy Award for Best Costume Design

Golden Globe for Best Actor

Laurence Olivier returns to the the duties of

actor/director/producer for his second Shakespearean motion picture adaption, his

praised masterpiece work of Hamlet.

For what would be surprisingly the first English language sound adaption of the

famed Shakespearean tragedy, the feature film swept through the cinematic word

with great commendation, becoming the most highly thought of adaptation of the numerous versions to be seen in the

decades since. It is also met its fair share of critics, primarily from the

scholars of the famous source material, chastising Olivier’s alterations needed,

as he saw it, to package the story into a consumable motion picture. Despite the

material and its star already being amongst the most well know in their fields,

this motion picture would somehow cement further the legacies of both, topping

its achievements off with being the first international film to win the

greatest prize at the Academy Awards.

Hamlet is Laurence

Olivier’s adaption of the Shakespeare tragedy about a Danish prince’s struggles

to avenge his father’s death at the hands of his uncle to gain the monarchy. In

the kingdom of Denmark Claudius (Basil Sydney) assumes the throne merely a

month after the death of his brother, the king, by marrying the queen, Gertrude

(Eileen Herlie). The melancholy prince, Hamlet (Olivier), is visited by the apparition

of his father revealing his death came at the hands of Claudius by way of

poison, setting Hamlet on a task to exact his revenge on his uncle. Hamlet

becomes psychologically more disturbed as he ponders the correct time of his

retribution, producing many around him to consider he has gone mad, while

Hamlet hints he knows the truth about his uncle. His vengeful road affects the

many around him, taking the lives of several, including his former love Ophelia

(Jean Simmons).

Hamlet is Laurence

Olivier’s adaption of the Shakespeare tragedy about a Danish prince’s struggles

to avenge his father’s death at the hands of his uncle to gain the monarchy. In

the kingdom of Denmark Claudius (Basil Sydney) assumes the throne merely a

month after the death of his brother, the king, by marrying the queen, Gertrude

(Eileen Herlie). The melancholy prince, Hamlet (Olivier), is visited by the apparition

of his father revealing his death came at the hands of Claudius by way of

poison, setting Hamlet on a task to exact his revenge on his uncle. Hamlet

becomes psychologically more disturbed as he ponders the correct time of his

retribution, producing many around him to consider he has gone mad, while

Hamlet hints he knows the truth about his uncle. His vengeful road affects the

many around him, taking the lives of several, including his former love Ophelia

(Jean Simmons).  Hamlet and Claudius’ unspoken contention comes to a head within

the duel between Hamlet and Ophelia’s brother Laertes (Terence Morgan) who

seeks revenge for Hamlet in his roles with the deaths of his loved father and

sister, who was driven to suicide because of Hamlet’s actions. Laertes and

Claudius’ plot to poison Hamlet becomes their undoing as the guilt stricken

Gertrude sacrifices herself for her son, while Laertes, after a lethal strike

from Hamlet, confesses Claudius’s guilt. Hamlet finally publicly justified for

his vengeance kills his uncle moments before succumbing to his own mortal wound,

closing with honored funeral of the fallen prince.

Hamlet and Claudius’ unspoken contention comes to a head within

the duel between Hamlet and Ophelia’s brother Laertes (Terence Morgan) who

seeks revenge for Hamlet in his roles with the deaths of his loved father and

sister, who was driven to suicide because of Hamlet’s actions. Laertes and

Claudius’ plot to poison Hamlet becomes their undoing as the guilt stricken

Gertrude sacrifices herself for her son, while Laertes, after a lethal strike

from Hamlet, confesses Claudius’s guilt. Hamlet finally publicly justified for

his vengeance kills his uncle moments before succumbing to his own mortal wound,

closing with honored funeral of the fallen prince.

As a motion picture, Hamlet

is a marvelous work of classic Shakespearean style that many would envision as

the quintessential mix of design, presentation, and acting of any Shakespearean

work. Olivier’s performance demands the attention of the screen with every

moment presence, even when he is the focal point of the frame. Olivier chooses

to center his adaption on Hamlet and his relationships with the other

characters when trimming back the original story, making this picture very

Olivier-centric.

The black and white cinematography utilizes what can be

observed as very plan settings delivering a melancholy aura presence that

penetrates the story. With the stylized choice, along with the masterful direction

and inspired acting you may become unaware of the overly classical Shakespeare

style that at time can be very cliché, as well as the rather simple set pieces

at times. Olivier frames the picture in interesting ways that make the images

speak far louder than the words being vocalized. Uses of framing characters within a series of

arches draw attention to characters, making them appear as empty as they are emoting

with the wonderful expression of the camera. Another creative use of framing

and blocking is depicted as characters interact of separate plains to evoking

the perception of dominance in a given situation. These examples as of staging

come from Olivier’s stage experience, but transfer seamlessly to his cinematic

vision in bringing Hamlet to the screen.

The most enthralling camera work comes in the scene of

Hamlet bestowing a play to his mother and uncle, a work that mirrors how

Claudius murdered the king as a indication of Hamlet knowing his uncle’s guilt.

As the play is being presented the camera pans around the audiences as the

gathering of characters watch the players, not realizing it recreating

Claudius’ devilish deed. In the long, carefully plotted camera movements we

observe layers of details as the players perform, Claudius and the queen

becoming increasingly mortified by the play, Hamlet observing their reactions,

and other audience members noticing the new king’s uneasiness. Olivier directs

this scene with the camera in lengthy, complicated movement going from one end

of the audience in a U-shape to the other end and back, focusing on many

characters, some from behind while seeing other in the background. It takes a

great deal of coordination as the camera and its crew sweep across the room and

back with the numerous actors needing to know when to be in place for action or

moving out of the way for the camera to achieve such an important and dramatic

shot.

Laurence Olivier at age forty was among the highest thought

of actors in British stage and screen at the time of production of Hamlet. Coming off of Henry V where he gained tremendous

critical praise for work as actor/director/producer in his cinematic

directorial debut, but Hamlet would

out do it. The choice of the film being shot in black and white was claimed by

Olivier to be an artistic choice comes into question as some stories state that

Oliver was having issues with film stock providers at the time when prestige

pictures were usually given the color treatment. In any case the film benefits

form the blacks and white with the use of shadows and drawing the attention to

the bright blonde head of the most troubled character on the screen, Hamlet.

Furthermore Olivier makes a second, uncredited contribution in the picture as

the haunting voice of Hamlet’s ghostly father’s deeply unsettling tone was

achieved by slowing and pitching down his recorded lines, delivering a very

effective presentation of the mysterious apparition.

His cast would be an ensemble of many classically trained

actors, including Basil Sydney and Eileen Herlie as Claudius and Gertrude. Herlie

was 11 years the junior of Olivier, her son in the picture, a fact that goes

rather unnoticed for those lost in the production. Among the vast many actresses

wishing to portray Ophelia, including Olivier’s own wife of Vivien Leigh, he

would cast a lesser known Jean Simmons who would deliver an Academy Award

nominated performance as Hamlet’s very trouble ex-love who is driven to death.

Many other future British stars of the screen can be found throughout the

production as well in smaller supporting roles, including an uncredited young

Christopher Lee in a non-speaking guard, among others, manifesting Olivier’s

drawing power in the British acting world at the time.

A product of the British producers Hamlet opened to worldwide acclaim becoming the greatest example of

exposure for a single production of Shakespearean work in the world for an

extended time. Box office numbers were very grand on both sides of the Atlantic

Ocean and film critics would praise the film for its great endeavor and

presentation of the classic work.

The feature presents to a running time of roughly two hours

and thirty minutes, which for a play that usually takes four hours means there

were many alterations to the original story, the source of the most negative

criticism for the film and its creator. Vast amounts of the story were cut back

to focus on Hamlet and his relationships, trimming much of the story’s

political plot points. Despite attempting to stay as true to the source

material as possible, much of the dialogue was cut back and select lines were

slightly altered for what Olivier thought would make more sense to the modern

viewer while still utilizing old English. The omission of characters

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern further would upset purists of the play. For many

Shakespearean fans they found the film an abomination to the source material,

while the general public found this version of Hamlet to be more than adequate as an adaptation fit within an

acceptable feature length timeframe.

The motion picture awards circuit gave the picture nearly all

of its greatest prizes. As an participant in the largest international film

festival of the time in Venice, Hamlet

took home the top award, which would later be titled the Golden Lion. In

England BAFTA named Hamlet the Best

Picture from any country, despite not winning for Best British Picture for some

odd reason. Meanwhile at the Academy Awards Olivier would be honored with two

wins, as producer he would received the Best Picture award, as well as his

statue for Best Actor, becoming the first actor to direct himself to an Oscar

win. However, Olivier did not attend the ceremony to accept his honors as he

was in England performing in a play in a play with Vivien Leigh at the time. It

was clear that despite Shakespearean critics the film community found Olivier’s

contribution to the source material and the cinema to be more than deserving to

receive all these great honors.

So if one goes into the film not a Shakespeare fan, although

you may still come out of it still not a Shakespeare enthusiast, you will come

out of it understanding better the heart of the tragedy and with a strong

respect for the man that made it possible. This version of Hamlet remains one of the highest regarded versions of the tale

that has been adapted numerous times over. Olivier would become the face of the

British classical acting around the world despite his critics. His work at

adapting Shakespearean material would not be over as he would return to the

task delivering Richard III in 1955,

closing out his cinematic Shakespeare trilogy.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment