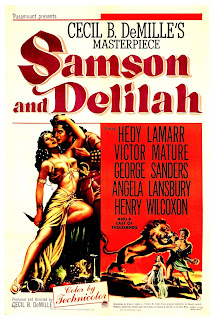

Samson and Delilah (1949)

Paramount Picture

Samson and Delilah is a Technicolor biblical epic

about a man endowed with superhuman strength and hero to an oppressed people who

is lured and betrayed by love. Strongman hero to the fraught Danite people

Samson (Victor Mature) rises to marry a Philistine noblewoman, Semadar (Angelia

Lansbury), only to witness her death during a Philistines against him. Samson

terrorizes his enemy while the jealous, seductive, and vengeful younger sister

of Semadar, Delilah (Hedy Lamarr), blames Samson for her sister’s death.

Delilah seduces Samson discovering his weakness, linking his God given strength

to a promise to not cut his hair, which she cuts off. Without his hair the weakened Samson is

capture by the, blinded, and enslaved by the Philistines, to the remorse of

Delilah. Ordered by Philistine ruler Saran (George Sanders) is brought to the

temple of the pagan god Dagon to be tortured for Philistine entertainment, but

time enough had passed for Samson to regrow his hair and return his strength. At

the temple with aid of Delilah Samson enacts his and God’s vengeance of the

Philistines by toppling the temple. For the climax Samson requests Delilah to get

away from the temple as he damages the pillars that support the temple,

bringing down large idol and collapsing the vast walls, claiming all within,

including Samson and Delilah who had stayed behind to watch her love.

Samson and Delilah is a Technicolor biblical epic

about a man endowed with superhuman strength and hero to an oppressed people who

is lured and betrayed by love. Strongman hero to the fraught Danite people

Samson (Victor Mature) rises to marry a Philistine noblewoman, Semadar (Angelia

Lansbury), only to witness her death during a Philistines against him. Samson

terrorizes his enemy while the jealous, seductive, and vengeful younger sister

of Semadar, Delilah (Hedy Lamarr), blames Samson for her sister’s death.

Delilah seduces Samson discovering his weakness, linking his God given strength

to a promise to not cut his hair, which she cuts off. Without his hair the weakened Samson is

capture by the, blinded, and enslaved by the Philistines, to the remorse of

Delilah. Ordered by Philistine ruler Saran (George Sanders) is brought to the

temple of the pagan god Dagon to be tortured for Philistine entertainment, but

time enough had passed for Samson to regrow his hair and return his strength. At

the temple with aid of Delilah Samson enacts his and God’s vengeance of the

Philistines by toppling the temple. For the climax Samson requests Delilah to get

away from the temple as he damages the pillars that support the temple,

bringing down large idol and collapsing the vast walls, claiming all within,

including Samson and Delilah who had stayed behind to watch her love.

What Samson and Delilah became was a lavish costume

drama of biblical proportions. With a production that took the plot as

seriously in writing and performance as a Shakespearean play the visuals were

to be big and bright. Technicolor cameras captured the elaborate and sometimes

revealing clothing on their lead actors, most notably Hedy Lamarr. Vast vistas

with hundreds of costumed extras in extravagant color had not been this vast

maybe since Gone with the Wind (1939).

Elaborate special effects using matte paintings, miniature trick

photography and sumptuous controlled chaos brings the excitement audiences had experienced

back when at the premiere of King Kong (1933). This $3.5 million DeMille

feature was going to be the biggest thing he had made to date.

What Samson and Delilah became was a lavish costume

drama of biblical proportions. With a production that took the plot as

seriously in writing and performance as a Shakespearean play the visuals were

to be big and bright. Technicolor cameras captured the elaborate and sometimes

revealing clothing on their lead actors, most notably Hedy Lamarr. Vast vistas

with hundreds of costumed extras in extravagant color had not been this vast

maybe since Gone with the Wind (1939).

Elaborate special effects using matte paintings, miniature trick

photography and sumptuous controlled chaos brings the excitement audiences had experienced

back when at the premiere of King Kong (1933). This $3.5 million DeMille

feature was going to be the biggest thing he had made to date.

The true appeal of the movie comes from its female lead in

Hedy Lamarr. The role called for character as beautiful and seductive as Lana

Turner and as jealous and cunning as Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.

Many did not know how vastly intelligent Lamarr was due in part of his

seductive good looks utilized as a traditional vamp style, but Lamarr knew how

to work herself to best effect for the role as Delilah. A character that vastly

exaggerates on the biblical tale Lamarr is tantalizing, treacherous, and

finally sympathetic in a performance delivering a vast amount of mass appeal to

the motion picture.

The true appeal of the movie comes from its female lead in

Hedy Lamarr. The role called for character as beautiful and seductive as Lana

Turner and as jealous and cunning as Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.

Many did not know how vastly intelligent Lamarr was due in part of his

seductive good looks utilized as a traditional vamp style, but Lamarr knew how

to work herself to best effect for the role as Delilah. A character that vastly

exaggerates on the biblical tale Lamarr is tantalizing, treacherous, and

finally sympathetic in a performance delivering a vast amount of mass appeal to

the motion picture.

Apart from Delilah the antagonist of the tale would go to

George Sanders’ performance as Saran. Sanders downplays the villous role with a

new kind of mastery. It was more common to see over the top performances for

such roles, but Sanders plays his part in a cool and calm manner of a man more

inwardly plotting than outwardly expressing. His performance gained a great

deal of praise and would inspire many historical drama villains to come with

his calm delivery and smooth British accent.

Apart from Delilah the antagonist of the tale would go to

George Sanders’ performance as Saran. Sanders downplays the villous role with a

new kind of mastery. It was more common to see over the top performances for

such roles, but Sanders plays his part in a cool and calm manner of a man more

inwardly plotting than outwardly expressing. His performance gained a great

deal of praise and would inspire many historical drama villains to come with

his calm delivery and smooth British accent.

Cecil B. DeMille was peaking once again in post war

Hollywood and helped to usher in a new era of biblical/historical epics to the

motion picture screen. With the advent of television as free home visual

entertainment lavish color costume dramas would be one of many formulas

Hollywood would utilize in the 1950s to keep audiences coming to the theater. Respect

was given to Samson and Delilah as DeMille made his cameo performance in the

upcoming drama Sunset Boulevard (1950) during the making of this feature.

In the scene DeMille, as himself, appears at work on the set from Samson and

Delilah when he greets Gloria Swanson’s character on a visit to the

Paramount Pictures studios. DeMille would outdo himself with his next features The

Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and remake of The Ten Commandments

(1956) showing just how he could keep turning out some of the best pictures of

the day. His work would inspire the industry to produce many more features in

the same vein resulting in classic epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus

(1960) following his death.

Cecil B. DeMille was peaking once again in post war

Hollywood and helped to usher in a new era of biblical/historical epics to the

motion picture screen. With the advent of television as free home visual

entertainment lavish color costume dramas would be one of many formulas

Hollywood would utilize in the 1950s to keep audiences coming to the theater. Respect

was given to Samson and Delilah as DeMille made his cameo performance in the

upcoming drama Sunset Boulevard (1950) during the making of this feature.

In the scene DeMille, as himself, appears at work on the set from Samson and

Delilah when he greets Gloria Swanson’s character on a visit to the

Paramount Pictures studios. DeMille would outdo himself with his next features The

Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and remake of The Ten Commandments

(1956) showing just how he could keep turning out some of the best pictures of

the day. His work would inspire the industry to produce many more features in

the same vein resulting in classic epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus

(1960) following his death.

Director: Cecil B. DeMille

Honors:

Academy Award for Best Costume Design (Color)

Cecil B. DeMille makes a rousing return to biblical epics in

this expansive adaptation of an Old Testament tale. With all the glory of

Technicolor, magnificent art direction, costume design, special effects, and a

bit of sex Samson and Delilah was the smash hit that dominated theater

box offices as the calendar turned to 1950. A passion project for DeMille that

took nearly decade and a half to bring to the screen the feature turned a small

Bible story into a spectacle that attracted large audiences looking to be wowed

by the power of the cinema.

Samson and Delilah is a Technicolor biblical epic

about a man endowed with superhuman strength and hero to an oppressed people who

is lured and betrayed by love. Strongman hero to the fraught Danite people

Samson (Victor Mature) rises to marry a Philistine noblewoman, Semadar (Angelia

Lansbury), only to witness her death during a Philistines against him. Samson

terrorizes his enemy while the jealous, seductive, and vengeful younger sister

of Semadar, Delilah (Hedy Lamarr), blames Samson for her sister’s death.

Delilah seduces Samson discovering his weakness, linking his God given strength

to a promise to not cut his hair, which she cuts off. Without his hair the weakened Samson is

capture by the, blinded, and enslaved by the Philistines, to the remorse of

Delilah. Ordered by Philistine ruler Saran (George Sanders) is brought to the

temple of the pagan god Dagon to be tortured for Philistine entertainment, but

time enough had passed for Samson to regrow his hair and return his strength. At

the temple with aid of Delilah Samson enacts his and God’s vengeance of the

Philistines by toppling the temple. For the climax Samson requests Delilah to get

away from the temple as he damages the pillars that support the temple,

bringing down large idol and collapsing the vast walls, claiming all within,

including Samson and Delilah who had stayed behind to watch her love.

Samson and Delilah is a Technicolor biblical epic

about a man endowed with superhuman strength and hero to an oppressed people who

is lured and betrayed by love. Strongman hero to the fraught Danite people

Samson (Victor Mature) rises to marry a Philistine noblewoman, Semadar (Angelia

Lansbury), only to witness her death during a Philistines against him. Samson

terrorizes his enemy while the jealous, seductive, and vengeful younger sister

of Semadar, Delilah (Hedy Lamarr), blames Samson for her sister’s death.

Delilah seduces Samson discovering his weakness, linking his God given strength

to a promise to not cut his hair, which she cuts off. Without his hair the weakened Samson is

capture by the, blinded, and enslaved by the Philistines, to the remorse of

Delilah. Ordered by Philistine ruler Saran (George Sanders) is brought to the

temple of the pagan god Dagon to be tortured for Philistine entertainment, but

time enough had passed for Samson to regrow his hair and return his strength. At

the temple with aid of Delilah Samson enacts his and God’s vengeance of the

Philistines by toppling the temple. For the climax Samson requests Delilah to get

away from the temple as he damages the pillars that support the temple,

bringing down large idol and collapsing the vast walls, claiming all within,

including Samson and Delilah who had stayed behind to watch her love.

This feature jumps out of December 1949 like a cinematic

fireworks show as a motion picture full of pomp, bright color and visuals, epic

prestige, and a grandeur that has not been observed since 1939, the golden year

of classic Hollywood. This feature easily inspires the many 1950s biblical/historical costume features that

peppered the decade and for it to emerge in late 1949 it bursts onto the screen

with pageantry of Hollywood yesteryear with the addition of a newly booming era

for American cinema. It is not a spectacular film, especially when compared to

the pictures to come, but it stands out in its time, helping to usher in a new

epic age of Hollywood feature that once again made going to the cinema a theatrical

event.

Cecil B. DeMille had dreams of producing a Samson and

Delilah feature as far back as 1935, after the success of another one of

lavish historical costume dramas Cleopatra (1935). With visions of the

plot being one of the grandest love stories in history DeMille began acquiring

rights to the 1877 French opera of the same name, as well as other literature

about the biblical story sourced from the Old Testament book of Judges. Hoping

to film in the new Technicolor process with stars Miriam Hopkins and Henry

Wilcoxon the project was put on hold for over ten years when in 1946 opportunity

arrived to finally revive the dream project. Paramount lacked enthusiasm for

cinematic retelling a “Sunday school story,” but DeMille would present an

artist rendering of a hulking Samson and a seductive Delilah to manifest the

sultry appeal of his vision earning his project the greenlight.

What Samson and Delilah became was a lavish costume

drama of biblical proportions. With a production that took the plot as

seriously in writing and performance as a Shakespearean play the visuals were

to be big and bright. Technicolor cameras captured the elaborate and sometimes

revealing clothing on their lead actors, most notably Hedy Lamarr. Vast vistas

with hundreds of costumed extras in extravagant color had not been this vast

maybe since Gone with the Wind (1939).

Elaborate special effects using matte paintings, miniature trick

photography and sumptuous controlled chaos brings the excitement audiences had experienced

back when at the premiere of King Kong (1933). This $3.5 million DeMille

feature was going to be the biggest thing he had made to date.

What Samson and Delilah became was a lavish costume

drama of biblical proportions. With a production that took the plot as

seriously in writing and performance as a Shakespearean play the visuals were

to be big and bright. Technicolor cameras captured the elaborate and sometimes

revealing clothing on their lead actors, most notably Hedy Lamarr. Vast vistas

with hundreds of costumed extras in extravagant color had not been this vast

maybe since Gone with the Wind (1939).

Elaborate special effects using matte paintings, miniature trick

photography and sumptuous controlled chaos brings the excitement audiences had experienced

back when at the premiere of King Kong (1933). This $3.5 million DeMille

feature was going to be the biggest thing he had made to date.

Over a decade removed from the initial concept the casting of

stars obviously had to change. For Samson DeMille had described the character

as a combination of Tarzan, Robin Hood, and Superman. Burt Lancaster turned

down the role due to a back injury and plans for bodybuilder turned actor Steve

Reeves failed to meet the needs of DeMille and his producers, eventually leading

to the casting of 20th Century-Fox actor Victor Mature as the

legendary strongman. Barrell chested,

ever striking a pose similar to a comic book hero Mature took on the project as

his greatest opportunity following a steady rise in his career since the end of

the war. Despite the big actor having severe fears on set, including of the

set’s wind machine and the possibility of wrestling a tamed and toothless lion,

a job left stunt man to rather poor effect, DeMille gets a decent performance

out of his star with direction that only a master filmmaker could get from a

troubled actor.

The true appeal of the movie comes from its female lead in

Hedy Lamarr. The role called for character as beautiful and seductive as Lana

Turner and as jealous and cunning as Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.

Many did not know how vastly intelligent Lamarr was due in part of his

seductive good looks utilized as a traditional vamp style, but Lamarr knew how

to work herself to best effect for the role as Delilah. A character that vastly

exaggerates on the biblical tale Lamarr is tantalizing, treacherous, and

finally sympathetic in a performance delivering a vast amount of mass appeal to

the motion picture.

The true appeal of the movie comes from its female lead in

Hedy Lamarr. The role called for character as beautiful and seductive as Lana

Turner and as jealous and cunning as Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.

Many did not know how vastly intelligent Lamarr was due in part of his

seductive good looks utilized as a traditional vamp style, but Lamarr knew how

to work herself to best effect for the role as Delilah. A character that vastly

exaggerates on the biblical tale Lamarr is tantalizing, treacherous, and

finally sympathetic in a performance delivering a vast amount of mass appeal to

the motion picture. Apart from Delilah the antagonist of the tale would go to

George Sanders’ performance as Saran. Sanders downplays the villous role with a

new kind of mastery. It was more common to see over the top performances for

such roles, but Sanders plays his part in a cool and calm manner of a man more

inwardly plotting than outwardly expressing. His performance gained a great

deal of praise and would inspire many historical drama villains to come with

his calm delivery and smooth British accent.

Apart from Delilah the antagonist of the tale would go to

George Sanders’ performance as Saran. Sanders downplays the villous role with a

new kind of mastery. It was more common to see over the top performances for

such roles, but Sanders plays his part in a cool and calm manner of a man more

inwardly plotting than outwardly expressing. His performance gained a great

deal of praise and would inspire many historical drama villains to come with

his calm delivery and smooth British accent.

Angela Lansbury would make an appearance as Delilah’s older

sister, despite being younger than Lamarr, in a role she fills in rather nicely

after actress Phyllis Calvert fell ill. Henry Wilcoxon, one of DeMille’s

favorite actors and the original vision for Samson in the 1930s, remains in the

picture as Ahtar, a direct Philistine rival to Samson manifesting the quarrel between

Philistine and Danites, the tribe term used to avoid the use of Israel or Jews to

make the film more conservative at the time .

Samson and Delilah would premiere in New York City

with vast reverence, including as a televised event. An opening musical overture

and closing composition gave the film a presentation a more theatrical feel of grandeur.

The film would run as a roadshow event for a month in New York before having

the event moved to Hollywood in advance of the general release in late March

1950. Viewing this film was meant to be an event and with all the pageantry the

film provided it would have very well felt that way. Samson and Delilah

quickly became the highest grossing film released in 1949. Eventually it rise

to become the highest grossing feature in Paramount Pictures history and for a

short time the third on the all-time list of box office income following Gone

with the Wind and The Best years of Our Lives (1946). The critical

success earned the picture two Academy Awards that generally praised it of its

lavish nature as a color feature, manifesting how the film lacked to supply

anything grand as an actual drama.

Cecil B. DeMille was peaking once again in post war

Hollywood and helped to usher in a new era of biblical/historical epics to the

motion picture screen. With the advent of television as free home visual

entertainment lavish color costume dramas would be one of many formulas

Hollywood would utilize in the 1950s to keep audiences coming to the theater. Respect

was given to Samson and Delilah as DeMille made his cameo performance in the

upcoming drama Sunset Boulevard (1950) during the making of this feature.

In the scene DeMille, as himself, appears at work on the set from Samson and

Delilah when he greets Gloria Swanson’s character on a visit to the

Paramount Pictures studios. DeMille would outdo himself with his next features The

Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and remake of The Ten Commandments

(1956) showing just how he could keep turning out some of the best pictures of

the day. His work would inspire the industry to produce many more features in

the same vein resulting in classic epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus

(1960) following his death.

Cecil B. DeMille was peaking once again in post war

Hollywood and helped to usher in a new era of biblical/historical epics to the

motion picture screen. With the advent of television as free home visual

entertainment lavish color costume dramas would be one of many formulas

Hollywood would utilize in the 1950s to keep audiences coming to the theater. Respect

was given to Samson and Delilah as DeMille made his cameo performance in the

upcoming drama Sunset Boulevard (1950) during the making of this feature.

In the scene DeMille, as himself, appears at work on the set from Samson and

Delilah when he greets Gloria Swanson’s character on a visit to the

Paramount Pictures studios. DeMille would outdo himself with his next features The

Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and remake of The Ten Commandments

(1956) showing just how he could keep turning out some of the best pictures of

the day. His work would inspire the industry to produce many more features in

the same vein resulting in classic epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus

(1960) following his death.

Clearly Samson and Delilah was a major influence on

Hollywood. As a film based on a few small chapters for the Bible it is rather

entertaining. Its lasting impact was DeMille’s vision to push movies back into

the realm of cinematic spectacle that Hollywood was celebrated for. European cinema

may have begun to inspire a darker, noir drama angle in American movies, but

DeMille reminded audiences of the simple joy of being taken on a journey to see

lavish settings and amazing visuals, allowing movies to be fun and

awe-inspiring.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment