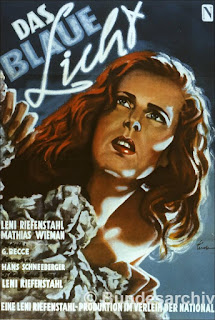

The Blue Light (1932)

1932 quietly marked the beginning to a brand new life for a German actress. Her earlier works had her act under the German director Arnold Fanck in a series of pictures set in the mountains where the young Leni Riefenstahl’s athleticism and beauty made her a very appealing person to cast. Under her own production company Riefenstahl would produce, write, direct, and star in her very own film which would catch the eye of the most powerful man in the country, setting her on a road that would forever affect her life. But in order for all that to happen Riefenstahl’s The Blue Light was produced manifesting just how much a visionary this young female was in European cinema.

The Blue Light (Das Blaue Licht)is the story about an outcast woman of a small town in Germany who is believed a witch, and how the people of the town take away the one thing that she adores in her life of solidarity. The story is very much in the tune of a fairytale; set in a time not yet long ago, but not yet modern; and in a place of not yet modern rationalists, and not yet completely superstitious. Our main character is Junta, played by Riefenstahl, who is an outcast of a small town at the base of a rocky mountain. She is condemned as a witch based on the fact that she is the only person that is able to scale the mountain’s dangerous face to see the source of a beautiful blue light that shines every full moon; all of the village’s men that try, fall tragically to their deaths. When a newcomer reaches town he is intrigued by Junta and the village’s reaction to her, he soon meets Junta and is inspired by her peaceful life. But when he follows Junta to the blue light, discovering the treasure trove that is this wonderful grotto of crystals which shine with the full moon’s light, he shares the news with the poor people of the town, informing them to mine it for the village’s financial gain. With the grotto pillaged of its natural beauty, Junta finds nothing else to live for, falling to her death while climbing down the mountain.

Once again proving the European cinema is in touch with deeper aspects of the human soul, The Blue Light is not a film of the lavish extravagance, but one of simple emotions. It is a tragic tale about the loss of natural beauty for petty financial gain. It is a story of conservative styles from a country whose future was headed by a leader looking to keep all things “pure.” In the picture there is nothing breathtaking. There is no lavish set decoration, minus the crystal grotto. There is no flashy new special effect. There is no sweeping cinematography. Most everything is kept very simple, allowing the actors to tell the story and portray the emotions. German cinema had only come so far in comparison to American film, but it is worth noting that this early talking picture in Germany was one of the first completely filmed entirely on location far from sound stages. This is made clear in the poor soundtrack and the obviously dubbed over lines which allowed the dialogue to be clearly heard by audiences. The audio quality is secondary to the movie with the fact that most of the film is told silently, without dialogue.

This was Riefenstahl’s directorial debut and already you can see trends in her style. She loved to film massive images, mainly the rocky face of the mountain where the drama of the story centers around. Somehow the way the mountain is presented, despite seeing it many times throughout the film, symbolizes something great and masterful. The mountain is beautiful and powerful, but with the work of the poor villagers looking to profit from it, the mountain is rapped of its most pure and beautiful aspects. Riefenstahl’s film is very slow with actions that take its time, but that is to express the power, beauty, and meaning the mountain has in the life of the Junta and the people.

The Blue Light would release to moderate success both with the box office and critics. Success was seen all throughout Europe, including the UK, and even in the United States. American critics praised skill and beauty of Riefenstahl, both as an actress and as the film’s director/producer, earning her the respect of the small number of people that admired European cinema. The picture even won a prize at the Venice Film Festival in Italy. The film received mixed reviews in Germany, but got praise from the man that would soon be the most powerful man in the country, Adolph Hitler, who would strongly admire the work of Riefenstahl.

Leni Riefenstahl’s career would greatly change when she heard Hitler speak at a rally in 1932, gaining admiration for his great oratory skill. With the two sharing like admiration towards each other, the pair met and Hitler would hire her to film great propaganda films for his cause, most famously Triumph of the Will, which would document the Nazi rally of at Nuremberg in 1933. But that is a future film to look at, and will be talked about later.

The Blue Light would be re-released years later in 1937, but for that release many Jewish names in the credits would be removed. The men removed included co-writers Carl Mayer and Béla Balázs, as well as co-producer Harry R. Sokal, simply because of their names. This manifested just how times were changing in Germany in that period. The picture would be re-released again in 1951 with a few edits by Riefenstahl, premiered in Rome to a warm audience for the filmmaker who lived through Nazi Germany.

The film marked a new beginning for the actress turned filmmaker. Her life would be forever changed by the work she would do for the next decade, but in time it would not be forgotten that she was a filmmaker, not a politician, and works such as this one is what made her a dignified member of European cinema.

.jpg)

Riefenstahl is more interesting than this film. She lived to be 101 years old, hardly made any films after WWII, and was she a victim or a perpetrator of Nazism? She certainly played the victim post-War, but that's a little too easy. Then you watch this arty film made just prior to her role as Nazi propagandist and want to give her the benefit of the doubt partly because she's so damn sexy.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, Fritz Lang was way better as a film maker and Hitler's first choice, and it took Lang about two minutes to decide to run away. What was so obvious to Lang but invisible to Riefenstahl?

The best take on Riefenstahl is to use her as a window into the positive side of fascism. Millions of Germans were not drawn to fascism because they wanted to offend the world with concentration camps and occupying armies. They wanted to use team-spirit and togetherness to build a better nation. It's the lesson of Triumph of the Will, which incidentally if my German is worth anything "Willen" should be translated as Wills-plural, emphasizing the community-spirit of the propaganda. How those positive patriotic impulses got perverted into rationalizations for violence and oppression is the great lesson to be learned from the Nazi experience.

Idealizing this film is a bit of a stretch, in my opinion. It had some nice moments, but was mostly pretty dull. Compare it to earlier or contemporaneous work by German directors like Lang with Metropolis and M, or von Sternberg with The Blue Angel, or Pabst with Pandora's Box and Diary of a Lost Girl. Or American works of the same vintage as Blue Light like Grand Hotel, or von Sternberg's American work with Blonde Venus and Shanghai Express.

I went to this picture just to get a look at Riefenstahl before her Nazi productions. Her film has deeper emotion (which American seemed to lack in their flashy pictures) and a simple style (which was different from German expressionism; also a happy difference to me).

DeleteWhat I get from this picture is the fact that I can see she has vision for her work. So did Lang. I would never take anything away from Lang, that is why I am not going to compare the two. Leni was just the one that fell under Hitler's spell after she heard him make a speech. The Blue Light was the film that got her noticed by Hitler, perhaps for the way her character was treated by the villagers and how she reacted to them, paralleling how Germany was treated by Europe after blaming WWI completely on Germany as seen in the Treaty of Versailles. I think you can possibly work that idea in our minds when we think of this film in Hitler's head.

Who knows how these two interacted? Riefenstahl went on to produce Triumph of the Will among other works for Nazi Germany and the rest was history. She didn't do much else being accused as a Nazi sympathizer, but I see her as a visionary filmmaker. Her films may not have been the best, even lacking in many areas, but she had grasp on something inside her creative mind, a vision on how powerful visuals can be in film.

We will see this all in Triumph of the Will which is what I am working on now.

Think we basically agree on The Blue Light. You won't see the mood an nuance in Triumph of the Will. You know who else had the life sucked out of him once he was a propagandist? Eisenstein. I loved Strike and his other stuff from the 1920's is a chore. Even Potemkin, I don't care how excited film students are supposed to get over a baby carriage rolling down stairs.

ReplyDelete